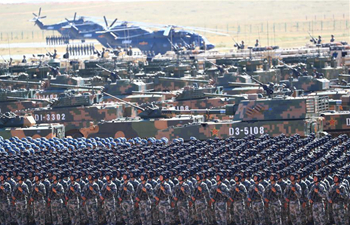

Photo taken on Aug. 8, 2017 shows a view of the celebration marking the 70th anniversary of the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region in Hohhot, north China's Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, Aug. 8, 2017.(Xinhua/Lian Zhen)

by Xinhua writers Li Laifang, Chen Lei, Zhang Yunlong and Urhan

HOHHOT, Aug. 8 (Xinhua) -- Former middle school teacher and principal, Enktobxin, an ethnic Mongolian, is Chinese Communist Party chief of Damao Banner in Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region.

Born into a family of herdsmen, Enktobxin, 50, grew up under the Party's ethnic policies and has made a success of his studies and his career.

"My Mongolian name means peace. I have grown up in a peaceful environment," he said.

This year is the 70th anniversary of the region, China's first with a system of regional ethnic autonomy, conceived to foster equality, solidarity and prosperity among all ethnic groups.

Enktobxin spoke only Mongolian at school. He learned Mandarin at college and now speaks it fluently. He obtained a master's degree in ecology from Inner Mongolia Agricultural University and a doctorate from Minzu University of China in Beijing.

Leaders of autonomous regions, prefectures and counties must be members of the relevant minority group and the governments must have a proper number of personnel from minorities.

In Damao Banner, 35 percent of Party and government officials come from minorities, according to Enktobxin. Ethnic minority officials currently make up about 33 percent of the regional total.

"These officials maintain ethnic solidarity, social stability and ensure economic growth," said Hao Shiyuan, member of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

COMMON PROSPERITY AND OPENING UP

Inner Mongolia's first high-speed railway -- from regional capital Hohhot to Ulanqab -- opened on Aug. 3. A link between Baotou City and Damao Banner's border port with Mongolia will open soon, a new route for China-European cargo trains, which already pass through two other border ports in the region.

In Xiramuren, Damao Banner, 80 percent of 2,200 former herders now live off tourism. Grazing has been banned since 2008 to restore grassland ruined by overgrazing and drought in the 1990s.

Only 80 km from Hohhot, the prairie has been a tourist spot for decades. A Tibetan Buddhist monastery is one of the main attractions.

Li Zhanfeng, 44, an ethnic Han, and his wife earn more than 100,000 yuan (15,000 U.S. dollars) a year renting 40 yurts to tourists.

"We get along well with local Mongolians. They bring visitors here for meals," said Li. To make more money, locals can set up commercial yurts near their homes as long as the grassland is not damaged.

Dolingar, deputy head of the township, said 1.2 million tourists visited last year and many local people have bought apartments in Hohhot where they spend winter and spring.

In Wutugou village of Ordos City, ex-farmers set up a haulage company with more than 50 trucks mainly transporting coal. This brought jobs to over 40 families.

There were 6 million poor people living in agricultural and pasturing areas of the region in the early 1980s. Now the number is just over half a million.

REVIVING TRADITIONS

Mongolian culture is thriving.

Narentongalag, in her 70s, makes Mongolian robes. She is busier than ever as young people who see money to be made, come to her to learn the craft. Traditional robes were listed as intangible cultural heritage in 2014. It is now fashionable to wear traditional robes with modern elements on occasions such as Nadam fairs, weddings and festivals.

"In the 1980s, Mongolian tailors were hard to find. Few young girls or wives learned," Narentongalag said. She told Xinhua that one robe can sell for 10,000 yuan.

The Manhan minor, a fusion of Han and Mongolian folk music in Jungar Banner,is becoming popular. The music dates back to the late Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) and has also been declared national intangible heritage.

"Ethnic solidarity means an exchange of cultures between ethnic groups," said Liu Haiping, head of the Manhan minor research institute in Jungar.

Ethnic education is receiving more financial support. Governments must hire no less than 15 percent of their staff from Mongolian language colleges each year.

"It is a good way to protect our culture," said Muren, "so long as the governments follow the rules."

Regulations protecting the prairie, Mongolian language and medicine are the backbone ethnic autonomy.

"We cannot lose our mother tongue," said Baojie, 47, a mother in Ordos. "We want our children to speak Mongolian, Mandarin and English."